THE JOURNEY TO AMERICA

Here is the story of what Patrick J. Dorgan experienced on the voyage to America and what happened when he landed on Ellis Island in New York on October 28, 1896.

STEP ONE: LEAVING HOME

For many, the decision to leave the “Old Country” was a family affair. Advice was sought and help was freely given by mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers, aunts, uncles, friends, and even entire villages. It was not unusual for an entire family to work for the money for a single family member to make the trip.

The practice of one member of a family going to America first, then saving to bring others over, was common. From 1900 to 1910, almost 95 percent of the immigrants arriving at Ellis Island were joining either family or friends. Sometimes the father would come alone to see if the streets really were paved with the gold of opportunity before sending for his wife and family. Sometimes the eldest son immigrated first, and then sent for the next oldest, until the entire family was in America. Often those who arrived first would send a prepaid ticket back home to the next family member. It is believed that in 1890 between 25 and 50 percent of all immigrants arriving in America possessed prepaid tickets. In 1901, between 40 and 65 percent came either on prepaid tickets, or with money sent to them from the United States.

Since all steerage tickets were sold without space reservations, obtaining a ticket was easy. Principal shipping lines had hundreds of agencies in the United States, and “freelance” ticket agents traveled through parts of Europe, moving from village to village, selling tickets. After 1900, in addition to a ticket, however, an immigrant had to secure a passport from local officials, and a United States visa from either the nearest American consular office of from the local consul at the port.

For many, simply getting to the port was the first major journey of their lives. They would travel by train, by wagon, on donkey, or even on foot. Sometimes travelers would have to wait days, weeks and even months at the port, either for their paperwork to be completed or for their ship to arrive, because train schedules were not coordinated with sailing dates. Assuming their paperwork was in order and a ticket had been purchased, some provision was usually made for the care of the emigrants who were forced to wait for the ship. Steamship companies were required by the governments to watch over the prospective passengers, and at most ports the travelers were housed in private boardinghouses. Some port cities even boasted their own “emigrant hotels.”

After the 1893 immigration law went into effect, each passenger had to answer a series of 29 questions (recorded on manifest lists) before boarding the ship. These questions included, among others: name, age, sex, marital status, occupation, nationality, ability to read or write, race, physical and mental health, last residence, and name and address of the nearest relative or friend in the country from which the immigrant came. Immigrants were asked whether they possessed at least $30, whether they had ever been in prison an almshouse, or an institution, or it they were polygamists or anarchists.

Steamship lines were also held accountable for medical examinations of the immigrants before departing the port. Most seaport medical examinations were made by doctors employed by the steamship lines, but often the examination was just too rapid to disclose any but the most obvious diseases and defects. Disinfection (of both immigrants and baggage) and vaccination were routinely performed at the ports. Finally, with questions answered, medical exams completed, vaccinations still stinging, disinfectant still stinking, the immigrants were led down the gangplank to first-class, second-class, or steerage accommodations. Steerage passengers walked past the tiny deck space, squeezed past the ship’s machinery, and were directed down deep stairways into the enclosed lower decks. They were now in steerage, their prison for the rest of their ocean journey.

STEP TWO: ON BOARD

Three types of accommodations on the ships brought immigrants to America: first class, second class, and steerage. Only steerage passengers were processed at Ellis Island. First- and second-class passengers were quickly and courteously “inspected” on board ship before being transferred to New York.

But steerage was enormously profitable for steamship companies. Even though the average cost of a ticket was only $30, larger ships could hold form 1,500 to 2,000 immigrants, netting a profit of $45,000 to $60,000 for a single one-way voyage. The cost to feed a single immigrant was only about 60 cents a day!

For most immigrants, especially early arrivals, the experience of steerage was like a nightmare. (At one time, the average passenger mortality rate was 10 percent per voyage.) The conditions were so crowded, so dismally dark, so unsanitary, so foul smelling, that they were the single most important cause of America’s early immigration laws. Unfortunately, the laws were almost impossible to enforce; steerage conditions continued to remain deplorable almost beyond belief. As late as 1911, in a report to President William H. Taft, the United States Immigration Commission said of steerage:

“Imagine a large room, perhaps seven feet in height, extending the entire breadth of the ship and about on0third of its length…. This room is filled with a framework of iron pipes, forming a double tier of six-by-two-feet berths, with only sufficient space left to serve as aisles or passageways….Such a compartment will sometimes accommodate as many as three hundred passengers and it duplicated in other parts of the ship and on other decks.

“The open deck space reserved for steerage passengers is usually very limited, and situated in the worst part of the ship subject to the most violent motion, to the dirt from the stacks and the odors from the hold and galleys….The only provisions for eating are frequently shelves or benches along the sides or in the passages of sleeping compartments. Dining rooms are rare and if found are often shared with berths installed along the walls. Toilets and washrooms are completely inadequate; salt water only is available.

“The ventilation is almost always inadequate, and the air soon becomes foul. The unattended vomit of the seasick, the odors of not too clean bodies, the reek of food and the awful stench of the nearby toilet rooms make the atmosphere of the steerage such that it is a marvel that human flesh can endure it ….Most immigrants lie in their berths for most of the voyage, in a stupor caused by the foul air. The food often repels them… It is almost impossible to keep personally clean. All of these conditions are naturally aggravated by the crowding.”

In spite of the miserable conditions, the immigrants had faith in the future. To pass the time a crossing could take anywhere from 10 days to more than a month depending on the ship and weathering would play cards, sing, dance, and talk, talk, talk.

Rumors about life in America, combined with stories about rejections and deportations at Ellis Island, circulated endlessly. There were rehearsals for answering the immigration inspectors’ questions, and hour upon hour was spent learning the strange new language.

By the time the tiring trip approached its long-awaited end, most immigrants were in a state of shock: physically, mentally, and emotionally. Yet, even with the shores of a New World looming before their eyes, even with tears of relief streaming down their faces, their journey was not at an end.

A final fear gripped their hearts: Would their new home accept or reject them?

STEP THREE: INSPECTION

Medical inspectors boarded incoming ships in the quarantine area at the entrance to the Lower Bay of New York Harbor. Ships were examined from 7 A.M. to 5 P.M. Vessels arriving after 5 P.M. had to anchor for the night.

The quarantine examination was conducted aboard ship and reserved for first – or second-class cabin passengers. U.S. citizens were exempt from the examination. Passengers were inspected for possible contagious diseases: cholera, plaque, smallpox, typhoid fever, yellow fever, scarlet fever, measles, and diphtheria. Few cabin-class passengers were marked to be sent to Ellis Island for more complete examinations. For example, in 1905, of 100,000 cabin passengers arriving in New York, only 3,000 had to pass through Ellis Island for additional medical checks. During the same year, 800,000 steerage passengers were examined at the island.

For steerage passengers, quarantine was simply a time of heightened frustration and ever-increasing anxiety.

After the visiting medical inspectors climbed down ladders to their waiting cutter, the ship finally moved north through the Narrows leading to Upper New York Bay and into the harbor. Slowly, the tip of Manhattan came into view. The first object to be seen, and the focus of every immigrant’s attention, was the Statue of Liberty. Perhaps her overwhelming impact can best be described in the words of those who saw her in this way for the first time:

“I thought she was one of the Seven Wonders of the World,” exclaimed a German nearing his eightieth birthday.

A Polish man said: “The bigness of Mrs. Liberty overcame us. No one spoke a word for she was like a goddess and we know she represented the big, powerful country which was to be our future home.”

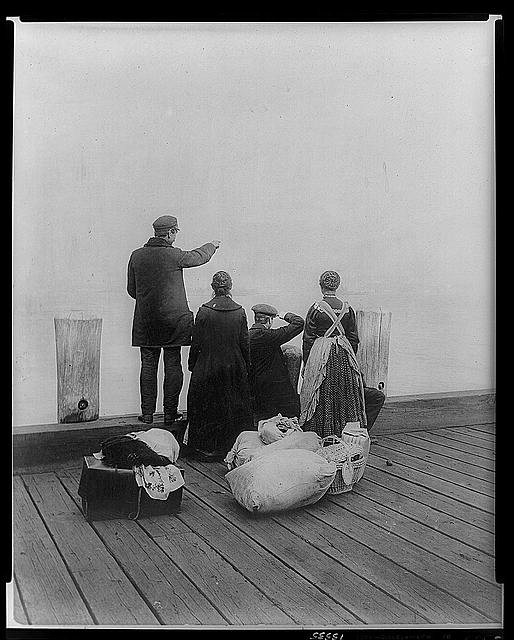

Just beyond the statue, about a half mile to the northwest, was Ellis Island. After the ship had docked in Manhattan, while cabin passengers were being released to the freedom of New York, steerage passengers poured across the pier to a waiting area. Each wore name tag with the individual’s manifest number written in large letters. The immigrants were then assembled in groups of 30, according to manifest letters, and were packed on the top decks of barges, while their baggage was piled on the lower decks.

Soon, very soon, they would arrive at the island’s landing slip and be led to the Main Building‘s large reception room. Here, at last, immigrants would take the final step in their journey to freedom in America.

When they finally landed, the ground still swaying like waves beneath their feet, the shrill shouts of a dozen different languages assaulting their ears, they met their first American, a nameless interpreter. In retrospect, it may be that these interpreters were the unsung heroes of the entire immigration screening process. Their patience and skill frequently helped save an immigrant from deportation.

The average number of languages spoken by an interpreter was 6, but a dozen languages (including dialects) were not uncommon. The record for a single interpreter was 15 languages.

One interpreter was Fiorello Laguardia, who would later become the famous mayor of New York City responsible for cleaning up the corruption of Tammany Hall. He worked at Ellis Island for an annual salary of $1,200 from 1907 to 1910. Interpreters led groups through the main doorway and directed them up a steep stairway to the Registry Room. Although they did not realize it, the immigrants were already taking their first test: a doctor stood at the top of the stairs watching for signs of lameness, heavy breathing that might indicate a heart condition, or “bewildered gazes” that might be symptomatic of a mental condition.

As each immigrant passed, a doctor, with an interpreter at his side, would examine the immigrant’s face, hair, neck, and hands. The doctor held a piece of chalk. On about 2 out of every 10 or 11 immigrants who passed he would scrawl a large white letter; the letter meant the immigrant was to be detained for further medical inspection.

Should an immigrant be suspected of mental defects, an X was marked high on the front of the right shoulder; a plain X lower on the right shoulder indicated the suspicion of a deformity or disease; an X within a circle meant some definite symptom had been detected. And the “shorthand” continued: B indicated possible back problems; C, conjunctivitis; Ct, trachoma; E, eyes; F, face; Ft, feet; D, goiter; H, heart; K, hernia; L, lameness; N, neck; P, physical and lungs; Pg, pregnancy; S, senility; and Sc, scalp. If an immigrant was marked, he or she continued with the process and then was directed to rooms set aside for further examination.

Sometimes whole groups would be made to bathe with disinfectant solutions before being cleared – not too surprising, considering how many were unable to bathe during the crossing. Again the line moved on. The next group of doctors was the dreaded “eye men.” They were looking for symptoms of trachoma, an eye disease that caused blindness and even death. (This disease was the reason for more than half of the medical detentions, and its discovery meant certain deportation.) Rumors of this particular inspection terrified many an immigrant, but it was over in a few seconds, as the doctor tilted the immigrant’s head back and swiftly snapped back the upper eyelids over a small instrument (actually a hook for buttoning shoes).

If immigrants had any of the diseases proscribed by the immigration laws, or were too ill or feeble-minded to earn a living, they would be deported. Sick children ages 12 or older were sent back to Europe alone and were released in the port form, which they had come. Children younger than 12 had to be accompanied by a parent. There were many tearful scenes as families with a sick child decided who would go and who would stay.

Immigrants who passed their medical exams were now ready to take the final test from the “primary line” inspector, seated on a high stool with the ship’s manifest on a desk in front of him and an interpreter at his side.

This questioning process was designed to verify the 29 items of information contained on the manifest. Since each “primary line” inspector had only about two minutes in which to decide whether each immigrant was “clearly and beyond a doubt entitled to land,” nearly all of the immigrants received curt nods of approval and were handed landing cards.

Most passed the test. (Only two percent of the immigrants seeking refuge in America would fail to be admitted.) After only a few more hours on Ellis Island, they were free to go. Their journey was nearly complete.

STEP FOUR: BEYOND ELLIS ISLAND

Those with landing cards in hand next moved to the Money Exchange. Here six cashiers exchanged gold, silver, and paper money form countries all over Europe for American dollars, based on the day’s official rates posted on a blackboard.

For immigrants traveling to cities or towns beyond New York City, the next stop was the railroad ticket office. There, a dozen agents collectively sold as many as 25 tickets a minute on the busiest days. Immigrants could wait in areas marked for each independent railroad line in the ferry terminal.

When it was reasonably near the time for their train’s departure, they would be ferried on barges to the train terminals in Jersey City or Hoboken. Immigrants going to New England went on the ferry to Manhattan. All that remained was to make arrangements for their trunks, stored in the Baggage room, to be sent on to their final destinations.

Finally! With admittance cards, railroad or ferry passes, and box lunches in hand, the immigrants’ journey to and through Ellis Island was complete. For many it had begun months or even years before. Some, of course, still had more traveling ahead of them – to the rocky shores of New England, to the Great Plains of the Midwest, or to the orange groves of California.

But whatever lay ahead, in their hearts they could read the invisible sign that proclaimed